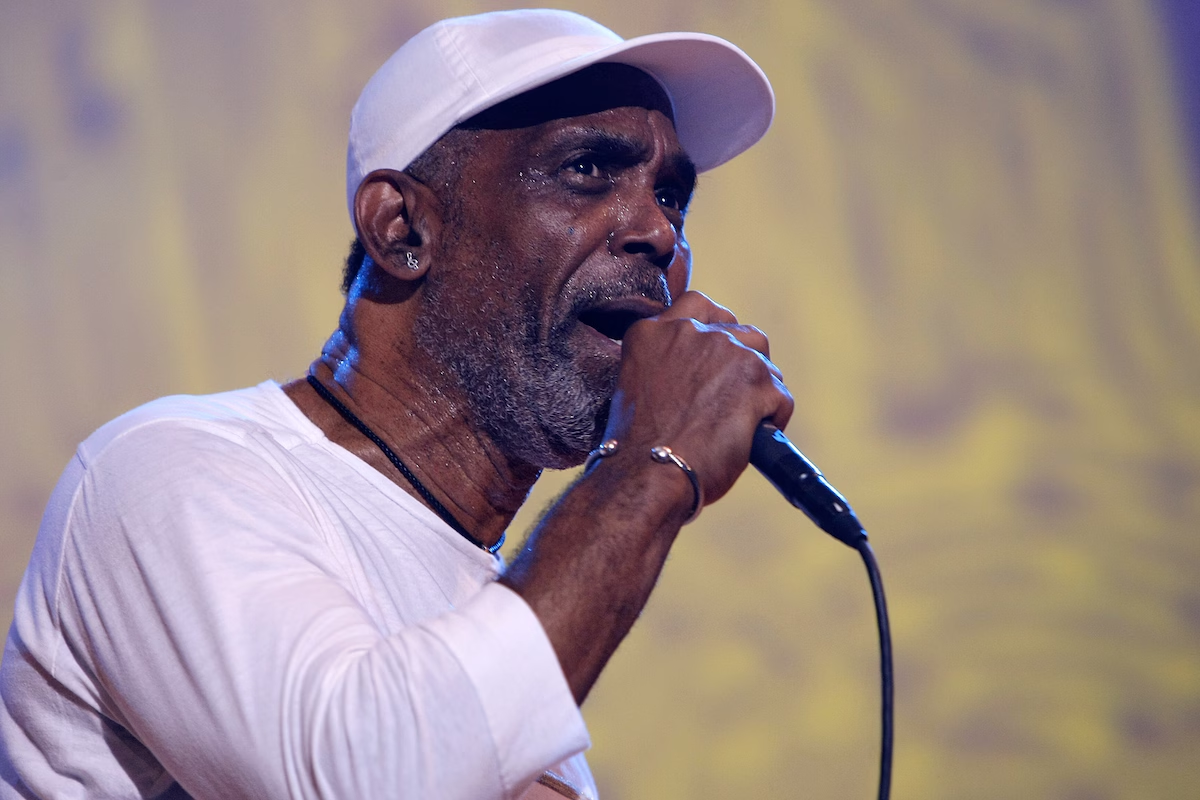

Frankie Beverly, exuberant singer-songwriter for Maze, dies at 77

Mr. Beverly, who also produced and played guitar, was the founder and driving force behind Maze, a seven- and then eight-piece group that Ebony magazine once dubbed “Black America’s favorite band.”

Beginning in the late 1970s, they developed a reputation as an energetic live

act, and rose to the top of the R&B chart with songs that were later sampled by hip-hop artists including 50 Cent, Wale, and the New York duo Rob Base & DJ E-Z Rock. Mr. Beverly concluded a farewell tour with Maze earlier this year, and made a guest appearance with the group at the San Jose Jazz Summer Fest in August.

While Maze never achieved the crossover success of Mr. Beverly’s musical lodestars Al Green and Marvin Gaye, synthesizer-laden songs such as “Love Is the Key,” “Southern Girl,” “Feel That You’re Feelin’ ” and “Joy and Pain” became staples of R&B radio stations and decades of house parties. The band’s most enduring hit, the jubilant 1981 single “Before I Let Go,” peaked at No. 13 on the R&B chart and was later covered by Beyoncé.

“There isn’t a cookout, not a wedding or family reunion in Black America where you won’t hear” the song, Essence magazine declared in 2017.

The band’s sound combined Philly soul with a sense of laid-back California cool, reflecting Mr. Beverly’s 1971 move from his hometown of Philadelphia to the San Francisco Bay Area. It also seemed to draw from Mr. Beverly’s childhood, in which he sang hymns and gospel songs at a Baptist church where his father was a deacon.

Wearing a ball cap and all-white outfit at concerts, Mr. Beverly seemed to adopt the persona of a secular preacher, urging listeners not to “judge a book by its cover” (“Color Blind”), asking why “we try and make each other sad” when “we could all be having so much fun” (“We Are One”), and wishing “happy feelings” on his audience in a song of that same name.

“Maze means magic and love,” he told Ebony in 1984. “Everybody is in this maze of life together — people of all types, colors and ages.”

The son of a truck driver and homemaker

, he was born Howard Stanley Beverly in Philadelphia on Dec. 6, 1946. He changed his name to Frankie around 12, when he heard Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, the doo-wop act behind “Why Do Fools Fall in Love.”

By his own account, Mr. Beverly began performing professionally around that same time, touring on the East Coast as a singer with the Silhouettes. “They lost their lead singer and a couple of the guys in the group were from my neighborhood,” he recalled in an online biography. “They’d heard that I could sing like Frankie Lymon and the next thing I knew, they were at my house asking my parents if I could go on the road with them.”

Mr. Beverly started a few doo-wop groups of his own

including an outfit called the Butlers that recorded for one of producer Kenneth Gamble’s early labels. But after hearing the soul and funk-inflected rock of Sly and the Family Stone, he started playing guitar and keyboards, renamed his band Raw Soul, and took the group west.

They joined the burgeoning San Francisco music scene with little success. As Mr. Beverly later remembered, he “learned to cook potatoes 15 different ways” and struggled to pay rent until Gaye’s sister-in-law caught one of Raw Soul’s performances and brought the band to the Motown singer’s attention.

Gaye invited them to open for him on tour in 1976, helped the group land a record deal with Capitol

and called Mr. Beverly into the studio for help on the 1977 chart-topper “Got to Give It Up.” (Mr. Beverly neglected to bring his guitar but played the milk bottle as a stand-in for the cowbell.)

Gaye also persuaded the band to change its name.

They landed on Maze Featuring Frankie Beverly. “I was looking for a one-syllable name, and Maze really attracted me because it is a puzzle,” Mr. Beverly told Jet. “I never saw us as just an R&B group or just a pop group either. It’s not easy to tag us.”

The name served as the title of their 1977 debut, which sold more than half a million copies and featured a memorable album cover that became the group’s logo — an illustration of a seven-finger hand, with each digit representing a member of the band. Mr. Beverly said he was the thumb.

The group went on to release seven more studio albums

including the R&B chart-toppers “Can’t Stop the Love” (1985) and “Silky Soul” (1989), and continued to fill theaters and arenas decades after the release of their last studio record, “Back to Basics” (1993). At the Essence Music Festival in New Orleans, they performed as the closing act for 15 straight years.

“The band’s shows are rehearsed rituals,

” New York Times music critic Ben Ratliff wrote in 2009, “working up to a rare and special audience feeling: deep, sentient serenity, not the usual kind of lose-yourself pop catharsis. … The songs slow the heart rate, establish hypnosis and spread altruism. They don’t take you to the other side of consciousness, or make you forget where you parked. But that’s all right.”

Mr. Beverly, who seldom discussed his private life, had a longtime relationship with San Francisco news anchor Pam Moore. He was sometimes joined onstage by his son Anthony, a drummer. Information on survivors was not immediately available.

In the band’s early years, Mr. Beverly said, he was often frustrated that Maze never found crossover success. Over time, however, he seemed to believe that the band’s niche status and loyal fan base gave it a certain kind of protection, enabling it to continue performing its brand of old-school R&B even as hip-hop came to dominate the charts.

“I wish more people did know who I was, but if it’s at the expense of me giving up this thing we have

, then I just have to wait until they find out,” he told the Baltimore Sun in 1994. “ ’Cause whatever we have, whatever this thing is that we seem to have a part of, it’s a cult kind of thing.”